Early History Of Vermilion

History tells us that the Erie Indians lived along the south shore of Lake Erie until their murderous extinction by the warlike Iroquois from upper New York State in 1655. Then around 1700 the Ottawas, Hurons (Wyandottes) and Chippewas gradually returned to the area for furs to sell to the French traders until they too were pushed out of their hunting and trapping grounds by the pioneering white man. Few Indians remained by 1800. One historian said, "Lake Shore Ohio was an Indian borderland. Indian habitation was a nervous, restless one punctuated by wars, international rivalries and disasters."

Native Americans

Native Americans

Prior to the first white settler in the Vermilion country we know little about the natives living along the river; we do know that they encamped along the river because it was there, and provided a friendly place to live, food from the stream and game from the woods and swamp. But the river was the main enticement that caused the Indians to settle along the highlands near the river. Fish easily caught from the stream provided a necessity of life. The river was the key to livability in the rugged and wild life of the native.

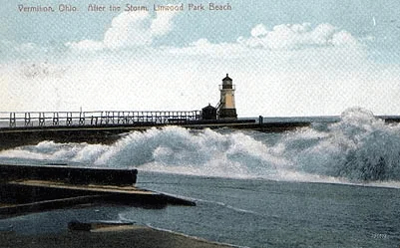

Linwood Park was a main village of the original Vermilionites in those far away years. Many relics were collected by a long time resident, Walter Ziegler, during his years there. Further up the river on the east bank beyond the railroads, Indian bones were unearthed in the construction of Vermilion Road. Other artifacts such as arrowheads, knives and tomahawks have been found throughout the township and village. The remains are now in collections and are faint flickers of Indian life most of us have forgotten in this modern world. In retrospect, these durable mementos leave us with a sense of primitive perseverance and respect for the Indian.

Early Explorers

The French Period, 1669-1762

French names abound from Vermilion westward: La Chapelle Creek, Huron River, Portage River, La Carne, La Carpe Creek, La Toussaint River, etc. Vermilion itself is of French derivation - vermilion, meaning red of course. Yet very little is known about French exploration along the south shore of Lake Erie.

Sanson's map of 1656 names and outlines the lake with reasonable accuracy, no doubt from Indian descriptions. It wasn't actually "discovered" until 1669 when Adrien Jolliet traversed the north shore west to east. That year two missionaries met Jolliet who told them of his passage on the lake. They recorded their visit to Lake Erie at Grand River near Long Point, where they spent the winter.On March 23, 1670, they erected a cross and took possession of our area in the name of the King of France. Francois Dollier de Casson and René de Bréhant de Galinée claimed possession of the area for France, on the basis that it was non-occupied. Their claim consisted of a certificate that they attached at the foot of the cross, along with the coat of arms of the King of France. A transcript of what they wrote on the certificate was sent to the King. Later, at the time of discussions between France and England in 1687, the French government sent the above transcript and Galinée's map to London as incontestable proof of France's rights to Lake Erie, Ontario, and the surrounding territory.

On the 26th of March, the explorers launched their canoes and paddled toward the west, hugging the north shore and camping each night on the beach. After 250 kilometers of paddling they reached the mouth of the Detroit River. Galinée honestly reported "Je ne marque que ce que j'ai vu. I note only what I've seen." He saw Point Pelee and the northernmost of the islands in western Lake Erie."

Dollier de Casson and Galinée, and many who followed later, purposely avoided the south shore because it was controlled by the Iroquois who had killed or driven out the Erie Indians in 1655 and who were mortal enemies of the French. Even as late as 1755, Bellin, engineer of the King for the French navy and drafter of an excellent map of the Great Lakes, inscribed the south shore of Lake Erie with the phrase "Toute cette coste n'est presque pas connue. All this shore is almost unknown."

With the fall of Quebec in 1759 and the ceding of New France to England in 1763, Lake Erie and Vermilion came under the rule of the King of England. Thus ended the French period with little or no written history of our area. Except for the ever remindful place names, probably given by coureurs du bois and voyageurs, not noted for their education or for recording their travels with maps or by the written word, we would never know that we are a former French jurisdiction which lasted over 90 years.

Pioneer's Life in the Wilderness

Pioneer's Life in the Wilderness

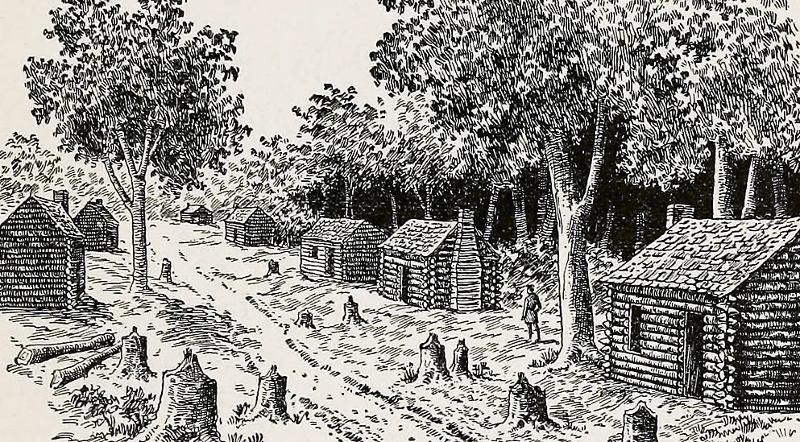

"We do not at all appreciate, we can hardly conceive, the inconvenience, the want, the suffering, the 'hard times' of the early settlers. Sickness added greatly to their hardships. Ague, 'chill fever,' and other malarial diseases incident to the opening of a new country, were prevalent. Sometimes whole families were prostrated, and often scarcely anyone remained in health to take care of the sick. Wild animals were annoying. Wolves, bears and foxes endangered their sheep, pigs and poultry, and deer, raccoon and wild turkeys damaged their crops. No roads, no mills, no markets and very scanty supplies at high prices of those articles of necessity, which had to be obtained from the East. Skins, furs and articles of food, from the necessity of the case, were used as legal tender. In fact, such was an early territorial law of Ohio. In 1792 a law was adopted regulating fees of civil officers, in which was the provision, 'That whereas the dollar varies in value in the several counties of the territory, some provision in kind ought to be made; therefore, be it enacted that for every cent allowed by this act, a quart of Indian corn may be demanded and taken by the person to whom the fee is coming as an equivalent for a cent, and at the same rate for a greater or less sum.' Taxes were not high, but it was difficult to pay them. Farm products brought but little return to labor. No markets. No markets."

The First White Men

One of the first explorers we know of and have solid evidence indicating that he was in Vermilion was Simon Kenton. He chiseled his name, S. Kenton 1784, on a boulder about 2 miles south of the river mouth on the southern border of the old Rossman farm in a spot about 600' east of the State Road. In 1937 the Centennial "Stone Committee" found it and took pictures. The stone now stands as a memorial to Kenton at the Ritter Library. Presumably, Kenton marked the boulder to substantiate his claim to a 4 square mile area surrounding the river mouth, a likely settlement someday. Kenton claimed similar areas throughout the State but lost his claims due to his lack of education. He was too early and too ignorant of drawing up legal claims of his discoveries. He died a poor man and might have been governor if he had had the proper background. As it was, though, he was an outstanding Indian fighter and explorer in the Ohio wilderness and his efforts added considerably to the opening of the country to the settlers. We do have the satisfaction of knowing that he was the first to find and realize that the Vermilion River would some day be the nucleus of a growing community. How right he was!

Settlers & Incorporation

Settlers & Incorporation

"Settling In"

Between 1808 and 1811 the first settlers struggled into the Township to claim land already surveyed by Almon Ruggles. The area was part of a tract offered by the State of Connecticut to the Fire Sufferers whose property had been plundered by the British during the Revolutionary War. A section of Connecticut's Western Reserve, it was appropriately called the Firelands. And using the name the Indians had given the river; the Firelands Company named Township No. 6, Range 20, Vermilion. However, so many years had passed and so much red tape was involved that most new arrivals were not the original Fire Sufferers, but those who had bought out claims of others. The first to arrive from the East was William Hoddy (or Haddy), who came alone from Connecticut, built his cabin by the mouth of the river and then returned East for his family. So far as is known he did not come back into the area.The following year the William Austins and Horatio Perry families arrived from New York; the George and John Sherods from Connecticut and Pennsylvania; and the Enoch Smiths from Connecticut. The Austins settled on the west bank of the river, the Sherods on land now known as Sherod Park. Sometime later in the year the Justin Thompson family came into the Township from Connecticut and settled on the Ridge.

Almon Ruggles came in with his family in 1810, as did Solomon Parsons, Benjamin Brooks, Barlow Sturges, Deacon John Beardsley and James Cuddeback. Peter Cuddeback and others came in 1811. According to the Firelands Pioneer, most came with teams.

As with the history of most settlements, the "firsts" have been carefully recorded:

The first house (cabin) was erected by the mouth of the river by William Hoddy in 1808; the first birth, John Sherod in 1809; the first marriage, Catherine Sherod to Burt Martin in 1814; the first frame house was Peter Cuddeback's (near the corner of Lake and Risden Roads) in 1818; the first stone house was William Austin's in 1821 and the first brick house was Horatio Perry's. The first commissioned Postmaster was Judge Almon Ruggles and the first doctor was Doctor Strong, although the first resident doctor was Dr. James Quigley in 1837. The first attorney, O. A. Leonard, announced his residency the same year.

Barlow Sturges began the first trading post and hotel. And together with the Austin family he ran the first ferry service across the Vermilion River. The first school was taught by Miss Susan Williams in a cabin on the lakeshore, in 1813. At about the same time another school was in operation on the Ridge and taught by Miss Addie Harris.

In 1818 the first organized religious society, the Presbyterian Church (later Congregational) was established. Ten years later the congregation built the first church, in an area just off Risden Road. This was the expected center of population.

In 1818 the Township government was organized with the following officers: Almon Ruggles, clerk; Peter Cuddeback and James Prentice, judges of election; Francis Keyes, John Beardsley and Rufus Judson, trustees; Jeramiah Van Ben Schoten and Horatio Perry, fence viewers; Peter Cuddeback lister and appraiser; Stephen Meeker, appraiser; Peter Cuddeback treasurer; George Sherod, Francis Keyes, William Van Ben Schoten and James Prentice, supervisors.

In the year 1820 the Vermilion township population was listed as 520.

Vermilion Village, 1837

Brownhelm Township

Brownhelm Township

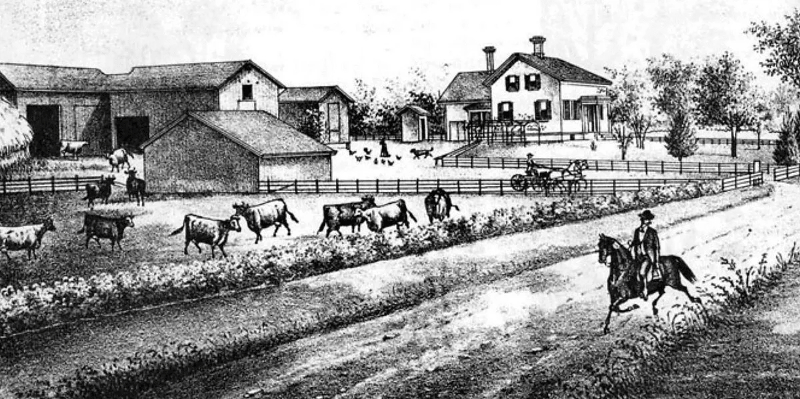

According to the William's History of Lorain County the first settler of Township No. 6, Range 19 (Brownhelm) lying along Lake Erie and then a part of Huron County, was Col. Henry Brown from Stockbridge, Mass. who arrived about 1816. He was accompanied by Peter P. Pease, Charles Whittlesey, William Alverson, William Lincoln, Seth Morse and Rensselaer Cooley, who assisted Col. Brown in building his house, a log house near the lake shore. Morse and Cooley returned to the East for the winter, the others remained on the grounds. The Township is named in honor of the leader of the original colony.Peter Pease became the first settler of Oberlin. On July 4th, 1817 the families of Levi Shepard, Sylvester Barnum and Stephen James arrived and were the first families to settle in the town. During the same year the families of Solomon Whittlesey, Alva Curtis, Benjamin Bacon and Ebenezer Scott arrived. In 1818 the families of Col. Brown, Grandison Fairchild, Anson Cooper, Elisha Peck, George Bacon, Alfred Avery, Enos Cooley, Orrin Sage, John Graham and others arrived. The first frame house was built by Benjamin Bacon; the first brick house by Grandison Fairchild in the summer of 1819. Until October 1818 the town was part of Black River; it was then organized as a separate township. Officers were Calvin Leonard, Levi Shepard and Alva Curtis, trustees; Anson Cooper, clerk; William Alverson, treasurer; Benjamin Bacon and Levi Shepard, justices of the peace. Lorain County was formed on December 26, 1822 with Brownhelm as a part. In 1827 Henry Warner started the Brownhelm quarry. Blocks were hauled on wagons to Vermilion where they were shipped via schooner.

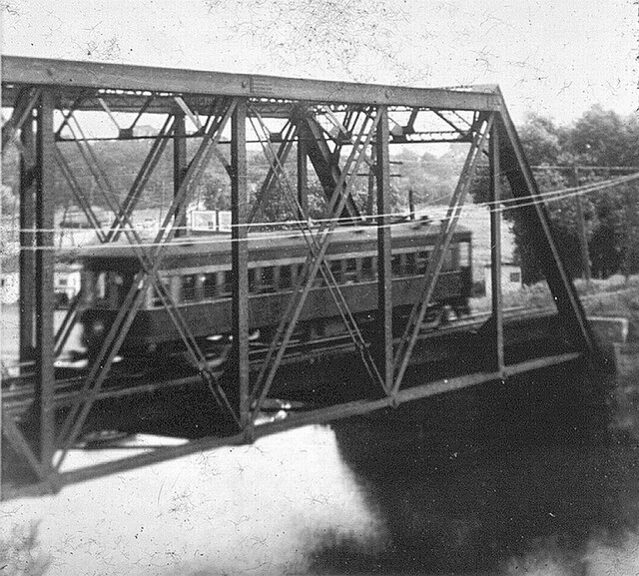

In 1819 Mrs. Alverson opened a school in her house. The 18 x 22 foot school was built on the brow of the hill (North Ridge Rd. near Claus Rd.) in the settlement and was named Strut Street School. In the early part of 1899 the brick school was built on N. Ridge Rd. The first class of nine -- 5 boys and 4 girls graduated in 1889. Brownhelm could also boast of a U.S. Post Office from November 6, 1878 to March 31, 1912 and a train station located at Brownhelm Station Rd, and Sunnyside Rd.

In the late 1950s the residents of Brownhelm voted to change zoning to permit the Ford Plant to build and, after losing the plant to Lorain in a heated court case, petitioned the Village of Vermilion for annexation. On December 21, 1959 the Village of Vermilion passed legislation to accept the petition and approximately 4,300 acres of Brownhelm Township, including Elberta Beach, became a part of Vermilion Village.

Vermilion River & Industries

Vermilion River & Industries

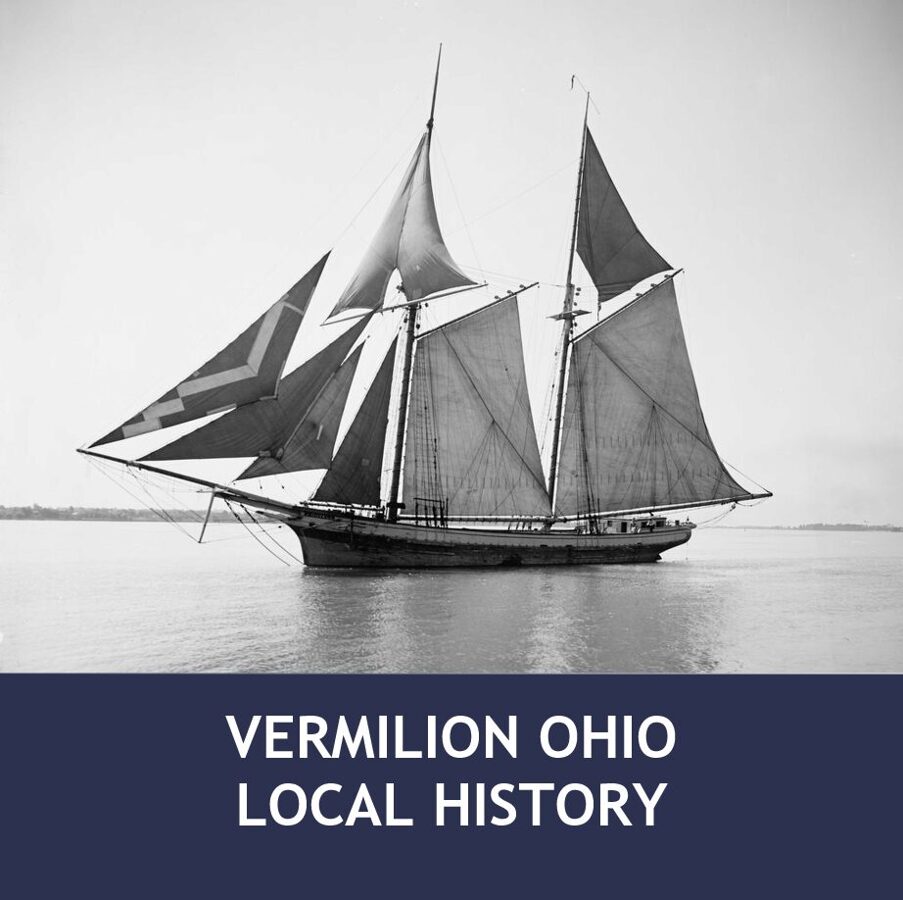

The Development of the River

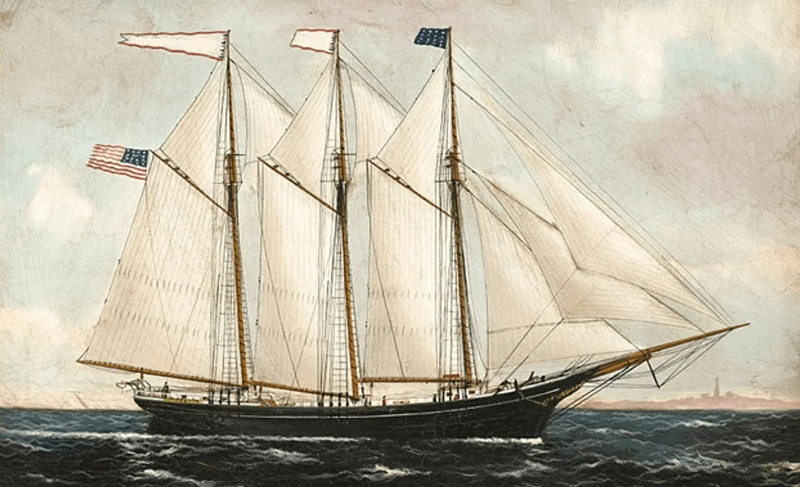

Captain William Austin was a man of energy and built the first schooner along the river in 1812. She was the FRIENDSHIP, a schooner of the times, about a fifty footer registered at 57 tons in Cleveland in 1817. Solomon Parsons built the second schooner, the VERMILION, in 1814 and registered in Detroit at 36 tons about 40 feet. Where these ships were built is not exactly known but the builders chose a flat place along the riverside. This most certainly had to be near the foot of Huron Street where the later shipyard stood when ship building became the main industry in the village. Small schooners were ideal for scudding along the lake shore bringing in supplies from Buffalo and other ports. They were as large as the natural river bars would allow and enough cargo capacity to supply the needs of the early settlements. The schooner was the "work horse" and a very important transportation means in the opening of the vast Great Lakes Country. They reigned supreme until a new form of transportation arrived along shore - the steam railroad.In 1840 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finished building the two piers at the mouth of the river which provided the bar depth builders needed to take crafts to sea. Thus began the "Golden Age" of ship building on the river, in tune with the great demand for shipping on the lakes. In a period of 36 years 48 large lake schooners were built. This provided jobs and growth for the community. The harbor was a beehive of activity and the sound of the maul on caulking iron was a musical note that rang throughout the valley.

One very interesting ship built in the Golden Age was the screw steamer INDIANA built by Burton S. Goodsell in 1848, the only screw steamer built in Vermilion. In June 1858 off Marquette, Michigan on Lake Superior she went down with a cargo of iron ore. Her loss was a mystery and was not explained until the Smithsonian Institute raised her in 1979; she had lost a blade from the four blade propeller and the subsequent vibration opened her wooden seams causing water to rush in and extinguish the boiler thus allowing her to sink. The Institute now has a fine exhibit in Washington, D.C. of the engine, boiler, propeller and other artifacts recovered in the salvage. The engine represents the finest original marine steam power plant in the country. This explains why the Smithsonian was anxious to recover the engine. The "Vermilion Display" is a permanent monument to ship building in Vermilion. No other city can boast such an honor on the lakes.

The Fishing Industry

With the abundance of fine fish in the lake plus the need for food, the early settlers took to the lake and shore with small boats and seines to reap the easy harvest. Soon they were sailing in deep water using gill-nets, trap-nets along shore to satisfy the market demand for fresh and salted fish. With the arrival of the trains the markets quickly expanded to the big cities. To meet this demand the steam tug emerged as the champion catcher of tons of delectable white fish, herring, pickerel and perch. Then came the powered net puller in 1900 making the steam tug the most efficient and profitable fishing method. The golden years were from 1890 to 1945 when the fish harvest on Lake Erie peaked making a lucrative livelihood for thousands of fisherman. Vermilion was home to the following commercial fish companies and their tugs:

- Kishman Fish Company

- Leiderheiser Fish Company

- Edson Fish Company

- Parsons Fish Company

- Driscoll Fish Company

- Southwest Fish Company

The Stone Industry

In the 1860s and 1870s considerable sandstone was shipped out of the harbor in schooners or barges. Two quarries, Brownhelm and Berlin Heights, shipped stone by rail to town where it was switched to the docks running from Exchange to Toledo Streets. Steam derricks transferred the stone from cars to the ships. Prominent quarry operators of the period were: Orange A. Leonard & Company, Summers & Harteep, and Worthington & Sons. Much of the building stone was used in rebuilding Chicago after the big fire there in 1871.The Lumber Business

Another lifeblood industry was lumbering. Prior to 1861 a large quantity of forest products, such as staves, ships' timber, firewood and furniture was shipped from the area. During the 1860s and 1870s a shortage of suitable timber developed in the immediate area surrounding the town. This made it necessary to import raw material. Throughout the period large quantities were shipped into the port in schooners from the upper lakes to be manufactured into sash, doors, blinds, molding, dressed flooring, siding and a variety of other related products. N. Fisher & Company was the largest dealer. They operated two scows (old schooners). Their steam mill was at the corner of Sandusky and Liberty Streets, the southwest corner. In 1876 Fisher & Company leased the lumber mill to J.C. Gilchrist & Company. They left Vermilion to establish a large steamship company. Some of their relatives stayed in the lumber business and are now operating in the Seattle country.Furnaces on the River - Lime Burning

Sometime around 1840 a lime kiln was built along the riverfront just north of Huron Street. The exact location is several feet north of Dr. Stack's house on the lakeshore. This furnace was a typical burner with a square sandstone base supporting a large iron stack. Limestone shipped down from the islands was loaded at the top with a skip-hoist that ran from the dock to the stack top. Horse power was used to hoist the stone cart. The burning flooded the town in a northeast wind with burning wood tinged with a lime aroma but the natives accepted the haze as a fact of life. The burnt lime was used to plaster many a house along the south shore of Lake Erie.Furnaces on the River - Iron

About 60 feet north of Huron Street along the riverfront were two stone foundations, round in shape 10' in diameter and 2' high. Around the foundations the ground was tinged red, the sign of iron ore. These two furnaces were the first stacks of the Geauga Iron Company of Painesville built in 1828-30. They had a dock and warehouse nearby on the river. Later they moved back on the ridge as the Huron Iron Company west of the State Road. This business operated for many years until coke made charcoal furnaces obsolete. The Huron Iron Company ceased operations in 1865.The Present River

In 1916 there were two yachts docked permanently in the river owned by Vermilionites; one was the IONA, a 35' glass cabin cruiser and the other was TOBERMORY, a 45' bridge-deck cruiser. Later, Harry Hewitt owned the NOMAD, a 36' powerboat he docked by the bridge. These three were the only pleasure boats in the steam in those days. Prior to those years the Rocky River sailboats would race to Vermilion on Labor Day for the annual "Big Time" in the little fishing port. Many a yarn was coined about the big mosquitoes that buzzed along the river.In 1916 the Vermilion Boat Club held their first South Shore Regatta, which attracted sailors from Toledo, Sandusky, Rocky River and Cleveland. Headquarters consisted of a tent in front of the waterworks. Free ice-cold lemonade was served to all yachtsmen. Many a river kid with the spirit of the day immediately became yachtsmen. It was a day to remember for the thousands of spectators that lined the docks and piers.

Currently the river supports some 8,500 yachts, small boats, many of them sail, which indicates some 350,000 passages. Sail for fun has replaced sail for work.

Industry

Aside from ship building, lumber, commercial fishing and the stone trade providing jobs along the riverfront, there have been several substantial enterprises formed in the town over the years. These have been basic living and growth industries essential for all communities:- Duplex Hot Water Heating Company

- The F.W. Wakefield Brass Company

- Dall Motor Parts Company

- South Shore Packing Corp.

- The Ford Motor Company

- The Howard Stove Company

- The Peasley Woodworking Factory

- Lithonia Downlighting

- Bettcher Industries

- Schwensen Bakery

- The Maurer Dairy

- The Vermilion News

Railways of Vermilion Ohio

Railways of Vermilion Ohio One of the first explorers of the Vermilion area was Simon Kenton (April 3, 1755 - April 29, 1836,) a famous United States frontiersman and friend of the renowned Daniel Boone, the infamous Simon Girty, and the valiant Spencer Records. Simon Kenton was born in the Bull Run Mountains, Prince William County, Virginia to Mark Kenton Sr. (an immigrant from Ireland) and Mary Miller Kenton. In 1771, at the age of 16, thinking he had killed a man in a jealous rage, he fled into the wilderness of Kentucky and Ohio, and for years went by the name "Simon Butler."

One of the first explorers of the Vermilion area was Simon Kenton (April 3, 1755 - April 29, 1836,) a famous United States frontiersman and friend of the renowned Daniel Boone, the infamous Simon Girty, and the valiant Spencer Records. Simon Kenton was born in the Bull Run Mountains, Prince William County, Virginia to Mark Kenton Sr. (an immigrant from Ireland) and Mary Miller Kenton. In 1771, at the age of 16, thinking he had killed a man in a jealous rage, he fled into the wilderness of Kentucky and Ohio, and for years went by the name "Simon Butler." Phoebe Goodell Judson grew up in Vermillion, Ohio. Her pioneer story begins when she married her husband Holden Allen Judson. After three years of matrimony they both decided "to obtain from the government of The United States a grant of land that "Uncle Sam" had promised to give to the head of each family who settled in this new country." With this the Judson's set out to pursue the vast uncultivated wilderness of the Puget Sound, which at that time was a part of Oregon. They departed March 1,1853. As Pheobe Judson recollects, "The time set for departure was March 1st, 1853. Many dear friends gathered to see us off. The tender "good-byes' were said with brave cheers in the voices, but many tears from the hearts."

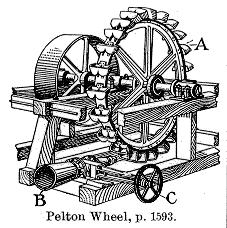

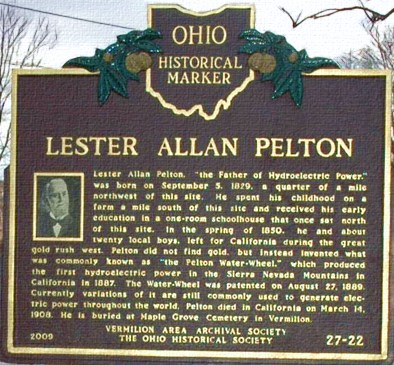

Phoebe Goodell Judson grew up in Vermillion, Ohio. Her pioneer story begins when she married her husband Holden Allen Judson. After three years of matrimony they both decided "to obtain from the government of The United States a grant of land that "Uncle Sam" had promised to give to the head of each family who settled in this new country." With this the Judson's set out to pursue the vast uncultivated wilderness of the Puget Sound, which at that time was a part of Oregon. They departed March 1,1853. As Pheobe Judson recollects, "The time set for departure was March 1st, 1853. Many dear friends gathered to see us off. The tender "good-byes' were said with brave cheers in the voices, but many tears from the hearts." Lester Allan Pelton (September 5, 1829 – March 14, 1908), considered to be the father of modern day hydroelectric power, is one the most famous inventors of American history. Pelton invented the impulse water turbine.

Lester Allan Pelton (September 5, 1829 – March 14, 1908), considered to be the father of modern day hydroelectric power, is one the most famous inventors of American history. Pelton invented the impulse water turbine. According to a 1939 article by W. F. Durand of Stanford University in Mechanical Engineering, "Pelton's invention started from an accidental observation, some time in the 1870s. Pelton was watching a spinning water turbine when the key holding its wheel onto its shaft slipped, causing it to become misaligned. Instead of the jet hitting the cups in their middle, the slippage made it hit near the edge; rather than the water flow being stopped, it was now deflected into a half-circle, coming out again with reversed direction. Surprisingly, the turbine now moved faster. That was Pelton's great discovery. In other turbines the jet hit the middle of the cup and the splash of the impacting water wasted energy."

According to a 1939 article by W. F. Durand of Stanford University in Mechanical Engineering, "Pelton's invention started from an accidental observation, some time in the 1870s. Pelton was watching a spinning water turbine when the key holding its wheel onto its shaft slipped, causing it to become misaligned. Instead of the jet hitting the cups in their middle, the slippage made it hit near the edge; rather than the water flow being stopped, it was now deflected into a half-circle, coming out again with reversed direction. Surprisingly, the turbine now moved faster. That was Pelton's great discovery. In other turbines the jet hit the middle of the cup and the splash of the impacting water wasted energy." The marker reads:

The marker reads: During the Revolutionary War in the late 1700s many Connecticut residents were burned out of their homes by the raiding British. To compensate these citizens for their losses, the Connecticut Assembly awarded the "Sufferers" 500,000 acres in the western most portion of the Western Reserve, which came to be known as the Firelands. Settlement was slow due to the remoteness of the tract and the difficulties in reaching it.

During the Revolutionary War in the late 1700s many Connecticut residents were burned out of their homes by the raiding British. To compensate these citizens for their losses, the Connecticut Assembly awarded the "Sufferers" 500,000 acres in the western most portion of the Western Reserve, which came to be known as the Firelands. Settlement was slow due to the remoteness of the tract and the difficulties in reaching it.

Louis Wells, a Cleveland contractor, began the Vermilion Lagoons project as a means of keeping his men busy during the Great Depression of the 1930s. By 1931 the first house and the beach house had been built and the lagoons were dredged and most of the wooden piling secured.

Louis Wells, a Cleveland contractor, began the Vermilion Lagoons project as a means of keeping his men busy during the Great Depression of the 1930s. By 1931 the first house and the beach house had been built and the lagoons were dredged and most of the wooden piling secured.

In 1919 a group of investors from the Cleveland area purchased a wooded property with 600 feet of Lake Erie frontage in tiny “Vermilion-on-the-Lake”, Ohio. They cleared the land, and using the very logs they felled, built an approximately 10,000 square foot private community center known as the Vermilion-on-the-Lake Clubhouse.

In 1919 a group of investors from the Cleveland area purchased a wooded property with 600 feet of Lake Erie frontage in tiny “Vermilion-on-the-Lake”, Ohio. They cleared the land, and using the very logs they felled, built an approximately 10,000 square foot private community center known as the Vermilion-on-the-Lake Clubhouse. The big bands of that era were soon accompanied by couples dancing on polished hardwood floors beneath a glittering globe. Those original hardwood floors, framed by the original log walls, are still there today. Soon, “Vermilion-on-the-Lake” became a summer playground and a sparkling jewel for well-to-do residents of western Cleveland.

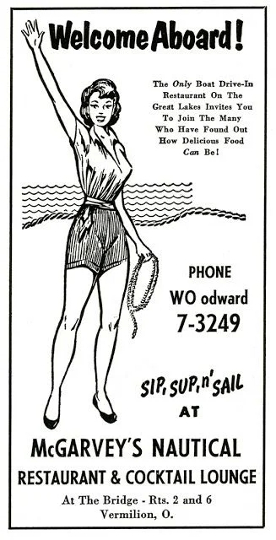

The big bands of that era were soon accompanied by couples dancing on polished hardwood floors beneath a glittering globe. Those original hardwood floors, framed by the original log walls, are still there today. Soon, “Vermilion-on-the-Lake” became a summer playground and a sparkling jewel for well-to-do residents of western Cleveland. Many people do not know, or remember that the restaurant known as McGarvey's was originally built, owned and operated by Charles Helfrich. That was in 1929, shortly after the new bridge was built across the river. The old bridge crossed a little south of the present location.

Many people do not know, or remember that the restaurant known as McGarvey's was originally built, owned and operated by Charles Helfrich. That was in 1929, shortly after the new bridge was built across the river. The old bridge crossed a little south of the present location. Mr. Helfrich operated a small boat and canoe rental business on the east side of the river. The proposed new bridge nearly touched his building and also diverted traffic away from it. So he purchased the land just north of the new bridge and built a restaurant and boat rental business there. Home cooked dinners, fish, chicken, sandwiches and homemade pies were the first attractions. Also served were the almost unheard of hot fish sandwiches, on Schwensen's bread. The business prospered and Helfrich's became a busy place. The canoe and boat business were also thriving. Canoeing on the river was a popular pastime in those days, especially on Sunday afternoons.

Mr. Helfrich operated a small boat and canoe rental business on the east side of the river. The proposed new bridge nearly touched his building and also diverted traffic away from it. So he purchased the land just north of the new bridge and built a restaurant and boat rental business there. Home cooked dinners, fish, chicken, sandwiches and homemade pies were the first attractions. Also served were the almost unheard of hot fish sandwiches, on Schwensen's bread. The business prospered and Helfrich's became a busy place. The canoe and boat business were also thriving. Canoeing on the river was a popular pastime in those days, especially on Sunday afternoons. In 1934 Mr. Helfrich died and two years later Mrs. Helfrich sold the enterprises to Charlie McGarvey's. After his death, Mrs. McGarvey sold her husband's business to

In 1934 Mr. Helfrich died and two years later Mrs. Helfrich sold the enterprises to Charlie McGarvey's. After his death, Mrs. McGarvey sold her husband's business to